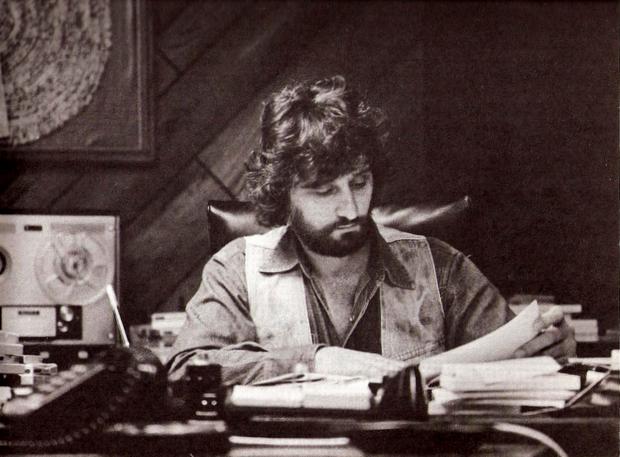

This week we lost of my all-time favorite country singer-songwriters, Steve Young. The writer of several classic songs made famous by some of the era’s biggest stars, Young was also a superb singer in his own right, and he has a string of excellent solo albums to prove it. On top of that, by many accounts (including my own experience) he was a wonderful man with a humble soul and a strong humanitarian streak. He also possessed lifelong ties to his Southern heritage that added richness and complexity to his songs.

Young died in Nashville, Tenn. on March 17, 2016 at the age of 73. He was in hospice at the time and under the close watch of his son, Jubal Lee Young.

“My father, Steve Young, passed peacefully tonight in Nashville,” Jubal wrote in a Facebook post. “While it is a sad occasion, he was also the last person who could be content to be trapped in a broken mind and body. He was far too independent and adventurous. I celebrate his freedom, as well, and I am grateful for the time we had. A true original.”

“I celebrate his freedom, and I am grateful for the time we had.”

Among Steve Young’s best-known songs is one of the most enduring anthems of the Outlaw era, “Lonesome On’ry And Mean,” a rambling-man song that Waylon Jennings covered in 1973. But that song was neither Young’s first composition nor the last anyone heard of him: his career stretches from the 1960s, when he cut the album Rock Salt & Nails (a record that featured Gram Parsons, Chris Hillman, and Gene Clark), all the way to the present, earning him accolades from critics (who have always loved his work) and his musical peers for his superb singing— a warm, dusty-edged baritone voice that can soar and sway— and guitar picking, which if anything has grown stronger over the years.

During all those years in-between, Young wrote and recorded a healthy number of knockout songs, among them “Seven Bridges Road” (covered by the Eagles and Eddy Arnold, among others), “Montgomery In The Rain,” and “Renegade Picker.” The last of the three is the title track of a 1975 album that showed Young itching with raw talent and standing on the precipice of greatness — something he achieved alone, despite the fact that he remained firmly on the outskirts of the country music mainstream.

A Child of the South

Young was born on 12 July, 1942 near Newnan, Georgia, and he also spent part of his childhood in Texas and Alabama. All that gave him some serious Southern roots, which run through the veins of many of his songs — and seem to tear at his soul as he struggles to figure out just what his legacy really is and where that leaves him. It certainly makes for songwriting that is at once stunningly beautiful, spiritual, and rippling with emotional turmoil.

After graduating from high school in Beaumont, Texas, Young ended up in Montgomery, Alabama — a city that itself is marked by a diverse and rocky heritage as the onetime capital of the Confederacy and the site of some famous Civil Rights protests. It was also the birthplace of Hank Williams, which comes up in Young’s song “Montgomery In The Rain,” an intense piece of work about returning to a town that doesn’t seem to want him around anymore.

Young played the bars and clubs around Montgomery before heading west to California. There he landed a recording contract with A&M, which released RoCK Salt & Nails in 1969—a folk-tinged album that stands among the best of the West Coast country-rock genre.

Young next signed with Reprise, which released the album Seven Bridges Road in 1972. When it disappeared quickly, the small New Mexico label Blue Canyon picked it up and re-released it. Along with the title track, which gained Young attention among West Coast artists like Bernie Leadon (of the Eagles) and Joan Baez, the album also included “Lonesome On’ry And Mean,” which intrigued Waylon Jennings enough to record it as the title track of a 1973 album. This gained Young quite a bit of notoriety in Nashville (Jennings also regularly praised him in the press), and Young eventually moved there. In 1975 he cut the album Honky Tonk Man for another small label, Mountain Railroad.

Renegade Picker

After Honky Tonk Man, Young was signed by RCA. The label released Renegade Picker in 1976, one of the great lost albums of the Outlaw period. The title track, though it appears to be about a musical rebellion, is actually an honest depiction of what Young himself was going through at the time— kicking drugs and alcohol. Other standouts include Guy Clark’s “Broken Hearted People (Take Me To A Barroom),” Willie Nelson’s “It’s Not Supposed To Be That Way,” and Rodney Crowell’s “Home Sweet Home (Revisited).”

Young followed Renegade Picker with No Place to Fall (another excellent album, the title track of which is a Townes Van Zandt song) two years later. He also appeared in the now-classic film Heartworn Highways, which included profiles and performances by such outlaw-era artists as Townes Van Zandt, David Allen Coe and Guy Clark.

After the RCA contract ended, Young was back on the independents. Rounder Records released To Satisfy You in 1981 and at the same time also released yet another version of Seven Bridges Road — this one featuring five cuts from the original Reprise release, four previously released cuts from the same sessions, and one new recording. This edition of Seven Bridges Road is an excellent collection, containing many of Young’s best-known songs, and it’s still probably the best introduction to his work.

Young toured extensively in the ’80s and ’90s, including stints in China and Mongolia on a US government-sponsored excursion. He also left Nashville and moved to Los Angeles, and that city served as his home base for several years.

He released further albums in Europe during the ’80s (Look Homeward Angel and Long Time Rider), and in 1991 the Texas-based label Watermelon Records signed Young and released Solo/Live. This is another great introduction to Young’s music, containing several classic titles (“Seven Bridges Road,” “Montgomery In The Rain,” “Long Way To Hollywood”) along with great covers such as John D. Loudermilk’s “Tobacco Road,” Mentor Williams’ “Drift Away,” and “The Ballad Of William Sycamore,” the words of which are a poem by Steven Vincent Benet.

Two years later came another fine album of new material, Switchblades of Love.

I connected with Young’s music in the 1990s, and I got to meet him during shows he played in the Bay Area at the Freight & Salvage and Slim’s. The man I met was low-key in the best way, friendly, and when he got on stage a knockout, his voice soaring and his songs digging in deep.

Fellow country artist James Talley wrote a nice post about Young on his Facebook page.

“Steve was a loner, and an uncompromising songwriter,” Talley wrote. “He was a powerful singer, and made a number of albums of his own for A&M and Warner Brothers Records. He was also a great interpreter of other people’s songs. He was a lifelong liberal and made no apologies for it. He never played the commercial music game. He said to me one time, ‘I would play the game, but I’ve never been able to figure out how to do it.’ It simply wasn’t in him. He remained true to his working class Alabama roots his whole life.

“He said to me one time, ‘I would play the game, but I’ve never been able to figure out how to do it.'”

“Last fall he was climbing the stairs in his home, lost his balance, fell and struck the back of his head. He was in intensive care at Vanderbilt Hospital for a month, and has been in various rehab facilities in Nashville over the past several months. But the recovery never really arrived. It was heartbreaking.

“Mine and my wife’s condolence goes out to his son Jubal Lee Young, a fine singer-songwriter in his father’s tradition, to Kim, and to the entire Young family. I have lost a wonderful friend, and we have all lost someone who was an artist in the truest sense of the word.”

Peace and love to Steve’s son Jubal Lee Young, his brother Kim Young, and all Steve’s friends and family.

This profile of Joe Diffie was adapted from the book Country Music: A Rough Guide, published in 2000 by Rough Guides.